I'm Jen Campo. And I'm currently sitting in my Houston office, where the temperature outside is listed as 91F, but I'm pretty sure that's an underestimation. In five days, I'll be walking about 3 kilometers from my dorm to the University Centre in Svalbard (part of the University of Norway) in 40F. And the sun will never set.

I'm headed off to meet my labmate,

Yuribia -- she's been in Svalbard for a month already. We'll be taking

the same class this July -- Arctic Terrestrial Quaternary Stratigraphy.

And there is an 8 day field excursion. I am very excited, and also very lucky. This past May, I returned to Houston after 33 days in Antarctica.

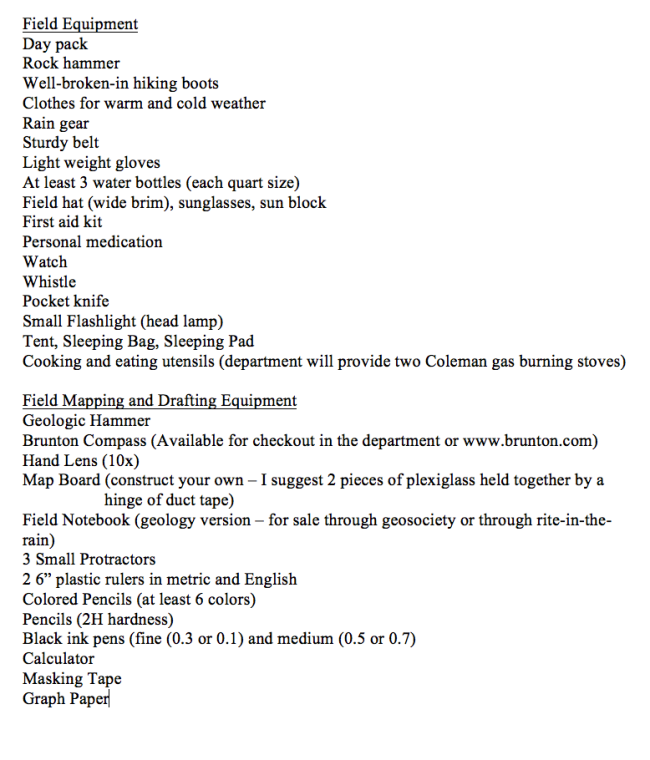

This post is about packing for the field. It's

something that I really wish someone had explained to me prior to my

first field trip to Inks Lake in 2011. I had zero camping experience

before I began my geology major, and this is the field list that you get

at the beginning of Field Methods at UH.

This

is a great list of field equipment, if you know what you're doing.

I, however, did not, and so I took "Day Pack" to mean backpack that

holds your tent, sleeping bag, tools, clothes, etc...and that's how I

showed up to Inks Lake. I completed my first foray of field work with a

backpack the size of a ten year old kid. It was slow, hot, and it took my attention off of the job at hand because I was so mad at how badly

I'd misinterpreted "Day Pack" (so mad, that I have no pictures of said

travesty, as I couldn't reach my camera in the depths of my huge pack). This was my biggest mistake in my early undergrad camping.

I now have the smallest backpack available. Witness its tiny size!

Four

good field lessons can be taught just from this picture alone. (1)

Crucial small backpack, with only enough room for 2L water pack (skip the three water bottles and invest in a bladder that fits in your pack), one extra

water bottle, lunch, sunscreen. (2) Bring a cool hat, not a stupid one

like I'm wearing. (3) Long sleeved field sheets, preferably with some built-in UPF protection (Magellan and Columbia are good brands) are key, and (4) If you intend to plank, don't do it on

something flat because it won't count and people will continue to remind

you of this years later.

For week long field trips conducted

through your geology department, that list is perfectly comprehensive. If you're going to the desert, you'll need tweezers. Don't forget

essentials like duct tape (to fix a mapboard), masking tape (to tape down maps in windy areas), and chapstick.

Is your

field work out of the country? For more than 4 weeks? You

need...really not that much else. Passport and adapters. That's the only extras. Here is what I'm packing for

Svalbard, which serves as a good corollary to what you should pack for something like

field camp.

Don't

forget your own towel. No one is going to let you borrow theirs.

Adapters and transformers are super important for foreign travel, but

perhaps more important for domestic and foreign travel is the AUX cable, with inputs at both ends. How

else will you control the music in the van you are riding in, or the car

you may have to rent if you end up with two free days in Chile, for example? On that note, if you are traveling out of the country, bring your driver's license in addition to your passport. You never know when you may need to rent a car. Also, know how to drive stick. Really.

Bathing suits always come in handy. One thing I'd wish I'd

known prior to field camp was that it behooves one to have some "going

out" clothes, like jeans. This lack of information meant that every

night spent out in town was done so in my dirty field clothes. Lame.

You will also need peanut butter. Lots of it. Reconstituted is easier

to pack, fresh easier to buy onsite, and I have learned the importance of having your own food stash

on long trips. If you are packing your own food and traveling into a different country, prepackaged is the only type of food that you will be allowed to take through customs in most places.

Yes,

this picture is shamelessly posed. Note the broken hand lens. Yours

should be in fine working order for the field, and you should always be using it! I like to bring multiple

sunglasses, in case I break a pair. I once briefly stole someone's

sunglasses on accident for an entire morning -- another reason to have a

backup. Accidental thieves may be among you!

Are your hands prone to dryness and cracking? You're not

sure? Take

ClimbOn!

with you. It's a life saver. You can't really see the little field

pack I have to hold my notebook, but it's great and fits on my belt (a

present from Nikki after I broke my first one and then whined about it

for an afternoon). The small flashlight is more appropriate for

boat-based field work. You never know what can happen at sea! Leatherman tools are OK, but heavy. Don't leave for

any fieldwork without your headlamp (not pictured here, because it's

the first thing I put in my bag). Speaking of bags, don't bring a

suitcase! EVER! Learn to pack a duffel.

My map board has held up for two and a half years

-- it should fit behind the space between your lower back and backpack.

That is how you should carry it. You don't want to waste time packing

it away in your backpack over and over again while you're out in the

field.

What else to take?

A

cool hat! My Alligator Queen hat has weathered many field trips.

Despite popular belief that you should change your shirt every day, the

same is not true in the field. If you have a week of field work, you

need a max of two shirts. More than a week, three. Same for pants.

However, you should have a different pair of socks, with liners to prevent blisters, and

underwear for EVERY day, otherwise...well...you will smell.

That

ziploc bag is filled with earplugs -- an indispensable tool for sleep,

in my opinion. A puffy down jacket! I learned this lesson the hard

way. Every day in Antarctica, I was cold. I bought that jacket as soon

as I stepped off the boat. I wore it right up until the minute my

plane landed in Houston (where it is sure to be useful for two, maybe

three, days per year), and its one of the best investments I've ever

made. Even Texas spots, particularly Big Bend, can get very cold at

night. I distinctly recall being terribly jealous of another TA's

awesome, puffy coat this past February at Inks Lake. The stowaway dog (unfortunately, dogs are not allowed on field trips -- Bo in Montana is the only exception) is sitting on

my rain coat, borrowed rain pants, and three base layers. Cold weather work is all about the

layers. Waterproof case for my phone and camera -- this is really only

important if you are doing zodiac (rubber boats that take you from the

ship to the shoreline) work.

Not pictured or listed, but still

important. Shower

shoes! Hand sanitizer for the field. Gum and/or tic-tacs (field breath

is uncomfortable, for you and whomever you are speaking to). Durable

camera. Your own coffee. A good knife. Compton, if you have room. For work >3 weeks, toenail clippers. Seriously. A

small hair dryer.

In reference to the field equipment list posted above, you're not going to need a calculator or graph paper. And three small protractors means

these guys (4 inch). I still carry a whistle, but I've never used it. Don't bother bringing your hammer to Inks Lake or Big Bend -- you won't be able to use it inside state or national parks.

Most important lessons learned over six departmental field trips (four involving stays in tents ranging from one to five nights), one session of field camp (five weeks), and one research cruise to Antarctica involving a five day stay in Punta Arenas, Chile:

Do not overpack. That is all.

Happy packing!